As we desire our cities to be clean, they must salvage, sort, sequester and refabricate the unending waste. Bholakpur in Hyderabad, does precisely that. All manner of solid waste – plastic, metal, raw hides and electronic refuse are processed, recycled and circulated back into the economy by a complex repertoire of techniques and tasks. Furthermore, these constitute the linchpin of livelihoods for many low income households of Muslims, Dalits (ex-untouchables) and Other Backwards Classes (OBCs) within the neighbourhood. Of nearly 18 bastis and colonies in Bholakpur, my work is predominantly situated in Mohammad Nagar – a basti constituted of over 120 households ranging from single room tenements to concrete two to three storey houses, built over time.

What intrigues me is how Mohammad Nagar’s history of settlement, does not fit with other bastis or colonies in Bholakpur. For instance, unlike Indira Nagar or Ranga Nagar, the future of this place was not accentuated by the government granting ‘pattas’ in the early 1970s. Mohammad Nagar’s story partly resonates with the story of occupation that one hears around Mahatma Nagar. Yet, once again, the story of Mohammad Nagar differs from Mahatma Nagar’s settlement history as after 1977, the latter was produced through G+1 housing layouts of 50 square yards and state granted loans to construct housing.

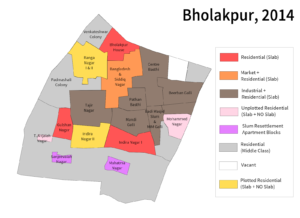

[A 2014 Map of Bholakpur by Hyderabad Urban Lab]

As I spent more time in Mohammad Nagar, it became clearer that the place had managed to resist any initiative to ‘clean up’, starting from the eighties – possibly, the fakiri its residents signed up for. Assembling Mohammad Nagar’s genealogy, meant assembling different stories.

One informant, Sheikh Chand Sajid, currently works for the Minorities Cell in Nizam College. He had been a part of Bholakpur Welfare Society at a time when the Congress MLA of Musheerabad in the nineties – M. Kodanda Reddy was also appointed Chairman of Hyderabad Metropolitan Development Association. Mr. Sajid, now on the brink of retirement, knew Bholakpur through land records he dug for a redevelopment project for Mohammad Nagar proposed by Musheerabad’s former MLA.

When I visited Mr. Sajid in August 2019, he was rather amused that I was asking him about Mohammad Nagar. For him, the place was up to no good, a judgment he had come to make since one night of conflict when his register of pattas was snatched by a bunch of people announcing that they did not agree to a given layout. The idea of a uniform 50 yard allotment did not receive the consensus my respondent imagined. In the idiom of betrayal, I was told that the place he wished to develop was ‘‘not ready in itself’’ even though he was convinced that a ‘‘Mumtaz Layout’’ created by the Municipal Corporation in the late fifties confirmed the land as government land. The claim was particularly important, even though he did not have the land records with him. This record meant that if the government wanted, it could have a free hand in deciding the fate of this place.

Another narrator of Mohammad Nagar’s land history, Khader Pasha, who claims to be an extended relative of the Azizia family of leather traders, and currently runs a school in the vicinity,told me that Mohammad Nagar thrives on WAQF land. In this version, the Police Action in 1949 compelled those at the Deccan borders to come to Hyderabad. The Quli Qutub Shah Masjid (officially called ‘Masjid-e-Kalam’ and colloquially known as ‘Badi Masjid’ in Musheerabad) and the surrounding vast open land offered the safe haven people sought then. The open (agricultural) land came under the Masjid, as a mode of earnings for its maintenance. As an extension of this narrative of the land of Mohammad Nagar being WAQF land, the construction of the community toilet was a byproduct of the Mutawali’s benevolence.

[Mohammad Nagar in Bholakpur, Map by Vanshika Singh and Kabeer Arora]

With so many storytellers and so many stories, the land question is indeed a puzzling one for Mohammad Nagar. Instead of going after the ‘authentic’ story of land, there is value in deciphering what each of these stories enables each of its story-teller to do.

Simultaneously, tracing the toilet story throws up the question of how a piece of community infrastructure can be so jinxed that it first takes nearly 4 years to get it running, only to subsequently waits to see the light of the day with over 3 years of no water supplied to it ?

From the likes of Sheikh Chand Sajid, to the likes of Khader Pasha, to the office help in Azad’s office – everybody speaks of a clean, sanitised and pending urban future that is due for Mohammad Nagar ; but when it comes to a basic toilet for its current inhabitants, its deficiency in terms of municipality not connecting it to water maps onto the bodies of the tenants unable to maintain a constructed community toilet!

There are two things that remain unresolved. One stems from an utterance of a key informant and raw hides trader – Wahab Bhai – who once said – ‘’Ek din agar bulldozer mangwayenge naa, toh saare Mohamamd Nagar ke asal log saamne aa jaa jayenge’’. Who are these ‘asal log’ of Mohammad Nagar ? Where are they if the tenants living in Mohammad Nagar do not form the body of real people ? What does this say about the agency of tenants grappling to claim urban life as citizens ?Are the ‘real people’ of Mohammad Nagar not signing up for a particular imagination of an urban future? How do the effects of this eschewal map onto the tenants who live in Mohammad Nagar? What template of development is at play, where if you do not sign up for a certain mode of urban existence, a group of people making life work in the city, struggle to get a dignified and safe space for bodily exegesis ?